It’s almost New Year now and a time when friends have their regular get together discussing the hits and misses of their lives over a dinner or a couple of drinks. This year also marks 10 years when I left my school to enter a new world .While contemplating a meeting to celebrate this, I realized that I am among the rare species of my batch who’s decided to not to pack my bags and flee India. There are just so many guys out there in the US that a get together there makes so much more sense than here.

What is that makes the average Andhraite so obsessed with the idea of going abroad or more precisely the US of A? He may not have any great visions on what to do when he goes there but he sure wants to land there, irrespective of the kind of work he does there. I have had friends working in petrol pumps and in bars in US which they would have never thought of doing in India. I attribute this to the mindset and the upbringing that has led them to believe that a Green Card ensures that the grass on the other side is always green.

I remember when I had given my job interview in ICICI Bank, I was asked how come I had done engineering and then moved over to MBA. I had answered that as a proper South Indian, I had become an engineer. May not be the best answer to give in an interview but that was the truth. South India generally suffers from a certain genetic disorder which forces them to become either engineers or doctors and I guess the problem is more accentuated in Andhra Pradesh.

The peer pressure of becoming an engineer and going to US is pretty high for the Andhraite. Right from childhood, he is constantly fed the mantra of “IIT” into his ears and by the time he is through with his primary school, he is ready to enter the haloed corridors of the IITs. In Andhra, students join coaching classes who tutor them to join Ramaiah or Krishnamurthy IIT coaching factories. These institutes then coach this select group of students for the IIT entrance exam. So, the crème-le-crème of the state is selected to train them into becoming IITians. For all those who do not enter IIT, we have a host of other engineering colleges which cater to this huge demand for engineers.

Post-engineering, most of the students take their GRE exam to do their M.S. abroad. Now this is of course a laudable attempt at higher education but you realize that the idea in many cases is not inspired by the concept of higher education but by the mere idea of going abroad and fulfilling the dreams that have been sown in their minds, for all these years, by their friends and family. They could be forgiven for assuming that it was for quality higher education. This argument must have made sense sometime back but now?

When one of my classmates had come down recently from Canada, he gave me gyan saying that the problem here is that people do not recognize you for your efforts unlike in the West and that there’s no strong incentive to work in such an environment. Nonsense, I say, what the hell am I doing here then? With a thought process like that and an outlook which fails to understand the progress we have made, I am really not surprised at such a remark.

The dowry amount is a strong incentive that drives parents to dream of their kids ensconced safely in California and elsewhere, while they spend days waiting for them to come back one day. So a B.Tech guy who commands a dowry price of say, Rs 10 lakh, would probably move into the 25 lakh+ category once he carries the “American abbayi” tag. I have seen palatial houses here constructed on the basis of the dollars sent back home but just a lonely couple waiting for their loved ones to come back one day and share their moments with them.

Friends tell me that this kind of exodus of people from one’s state is not a solitary case and they cite the classic example of Kerala where at least one member of every family works in the Gulf (more than 2 million of them in the Gulf). Numerically and statistically, the argument works but honestly, there’s no comparison between the 2 states when you look at the reasons for this. Majority of the Keralites employed in the Gulf work at lower strata in the Gulf society and do not represent the well-to do crowd there. This emigration is more to do with Kerala’s vehement anti-employment policy, which encourages people to look for other avenues for jobs.

But it is not my point that this flight of intellectual capital is wrong and that people should not leave our shores. After all, merely working in India does not make us any more patriotic. I am not even deriding the claims of subsidised technical education at the IITs though that can also be avalid point.Working outside India is a natural consequence of globalization where we export our most abundant natural resource-labour. This has also lead to a great deal of knowledge transfer that has been of immense utility to the country. The NRI remittances from there also contribute to a great deal in sustaining their families, though I also believe that this inflow (along with the IT pay packages) has fuelled to quite an extent Hyderabad’s inflationary real estate prices.

There’s something less tangible that we probably lose as we stay away from our roots; something I feel at a micro level when I am staying about 1500 odd km from my hometown. My point rests at a more emotional level about a sense of loss and erosion of identity that happens over a period of time.This becomes more pronounced as each generation goes by; somewhere akin to the loss of a certain genetic material found in us. Maybe it’s a purely emotional thought but as we go further away from our roots, there exists a certain loss of identity which is hard to regain as time passes.

I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it - Voltaire

Sitemeter

Friday, December 22, 2006

Friday, December 15, 2006

The Tata Singur Impasse

The Singur controversy has attracted a strange set of bedfellows-the Tatas and the Left Government on one side representing the so-called “capitalists” and Mamta, BJP, Medha Patkar on the other representing “people’s interests”. Politically, the Rajas and Yechurys are conveniently silent and the entire issue has become Buddha’s lone fight. It's best to ignore Mamta madam’s theatrical outbursts and so I am keeping aside the politics involved here, though the clincher in the deal may be politics.

Singur is a village about 50 km northwest of Kolkata and is predominantly an agricultural area. The Tatas want to set up their small car unit here and have estimated about 997 acres of land for this. 950 acres has already been agreed and the remaining 47 acres is still being negotiated, but we know what the result would be. The compensation agreement entails owners of single-crop land to receive Rs 8.4 lakh per acre and Rs 12 lakh an acre if the land was used for double-cropping.

The issues involved, broadly, as I understand are:

1.Agricultural land for industrialization:

Most of the land acquired for the purpose of setting up the land is agricultural and fertile land. A pro-Left article claims that this is because of paucity of non-agricultural land at West Bengal. But Bengal accounts for only 3.8% of the total agricultural land in India, so that argument does not cut ice. Even if it is so, why are the Tatas insisting on acquiring this land? For a company known for its CSR, this seems like an aberration unless they take pains to explain their decision. Is the locational advantage so tremendous that the company has to set up base there or is it because of the sops being offered by the West Bengal Government?

2.Total Land Area Required:

If a Maruti Udyog with an installed capacity of 3.5 lakh cars a year requires a total land area of 300 acres, do the Tatas require three times that much land for producing only one lakh cars? Maybe they do but then shouldn’t they be transparent about it and tell the farmers and the public what they wish to do with this land? Surely, their PRO can do a better job about this rather than maintaining a dogged stance on this aspect and insisting on going ahead with the same plans.

3.Compensation payment:

There seems to be a fairly good consensus that the compensation package paid by the Government is more than adequate and more than 94% of the land owners have agreed to sell of the land because of this. But then, it’s not just the land owners who are involved here. After the land reforms instituted here under Operation Barga, most of the land rests in the hands of land owners while the revenue/produce is shared between the land owners and the share croppers (who get the land cultivated). There are also the farmers who do the actual tilling on the land and work as daily wage earners – all this makes it a more elaborate sub-contracting set-up among owners, croppers and workers. It needs to be ensured that all the three concerned parties are compensated for this sale adequately and not just the land owners.

4.Employment opportunities for the displaced:

As mentioned earlier, there are several daily wage workers who would lose out when this land goes to corporates. This loss of livelihood may have to be compensated by the company in terms of employing them in the company or elsewhere and would again require them to train the workers in other skills. The Tatas reportedly plan to train workers for this but past records of most land acquisitions do not give us much of a comfort. We do not have a system to evaluate the effectiveness of the compensation provided and the aftermath of such acquisitions. There have been cases where the displaced receive monetary compensation but their future remains uncertain due to lack of investment knowledge and absence of any other skill sets.

Currently, agricultural land in India cannot be sold for non-agricultural purposes, so such sales happen only when the government comes into the picture by a back door approach of acquiring land from rural areas and selling it to corporates. But should they involve themselves in such transactions only for public utilities like roads, flyovers etc. or should they do this even for sale to private individuals? There may be people who do not wish to sell the space but are forced to do so because the Government thinks it is for the “greater good”.

Do we give farmers the right to sell their land to anyone they wish to? Since right to Property is not a Fundamental right (it was removed under the 44th amendment Act in 1978 by the Janata Party), it becomes an arbitrary call by the government. This naturally depresses the land prices due to lack of buyers and becomes a liability for farmers who want to move out of agriculture. The very idea of this law was to prevent reduction of agricultural land and acquisition of land by loan-sharks and corporates.

However, freeing land sales may also lead to the land going back to the hands of money lenders and zamindars – again a reversal of the process of democratization of land. Moreover, we cannot reduce the worker’s dependence on agriculture suddenly without adequately training him otherwise. And if you train him, will he be gainfully employed?

At a more macro-level, there’s a school of thought which believes that since agricultural productivity is low, the land should be utilized where it gives the best revenue. An argument for effective utilization of resources but I’m not too sure about this approach. A blogger has accused the middle class of romanticizing the notion of rural agriculture when it is totally a loss making concept.

Is agriculture a viable option, especially, considering the dependence of farmers on so many extraneous factors in agriculture like monsoon, price fluctuations, seed quality etc? With stagnant agricultural growth and lack of governmental interest (except in WTO forums and election manifestos), we may require providing farmers with this freedom to sell so that farmlands are easily disposable. This ease of disposal also brings in more buyers and increases the land rates.

However, any such decision must also take into account the social and environmental fallout of rapid and massive industrialization. Somewhere, we need to take a middle path between environmental and economic considerations. We cannot look at either of them in isolation and the challenge is to marry the two interests such that any “collateral damage” is limited. Future wars may be fought on energy and food security, as the Iraqi wars and African conflicts show and we need to be ready for that.

Singur is a village about 50 km northwest of Kolkata and is predominantly an agricultural area. The Tatas want to set up their small car unit here and have estimated about 997 acres of land for this. 950 acres has already been agreed and the remaining 47 acres is still being negotiated, but we know what the result would be. The compensation agreement entails owners of single-crop land to receive Rs 8.4 lakh per acre and Rs 12 lakh an acre if the land was used for double-cropping.

The issues involved, broadly, as I understand are:

1.Agricultural land for industrialization:

Most of the land acquired for the purpose of setting up the land is agricultural and fertile land. A pro-Left article claims that this is because of paucity of non-agricultural land at West Bengal. But Bengal accounts for only 3.8% of the total agricultural land in India, so that argument does not cut ice. Even if it is so, why are the Tatas insisting on acquiring this land? For a company known for its CSR, this seems like an aberration unless they take pains to explain their decision. Is the locational advantage so tremendous that the company has to set up base there or is it because of the sops being offered by the West Bengal Government?

2.Total Land Area Required:

If a Maruti Udyog with an installed capacity of 3.5 lakh cars a year requires a total land area of 300 acres, do the Tatas require three times that much land for producing only one lakh cars? Maybe they do but then shouldn’t they be transparent about it and tell the farmers and the public what they wish to do with this land? Surely, their PRO can do a better job about this rather than maintaining a dogged stance on this aspect and insisting on going ahead with the same plans.

3.Compensation payment:

There seems to be a fairly good consensus that the compensation package paid by the Government is more than adequate and more than 94% of the land owners have agreed to sell of the land because of this. But then, it’s not just the land owners who are involved here. After the land reforms instituted here under Operation Barga, most of the land rests in the hands of land owners while the revenue/produce is shared between the land owners and the share croppers (who get the land cultivated). There are also the farmers who do the actual tilling on the land and work as daily wage earners – all this makes it a more elaborate sub-contracting set-up among owners, croppers and workers. It needs to be ensured that all the three concerned parties are compensated for this sale adequately and not just the land owners.

4.Employment opportunities for the displaced:

As mentioned earlier, there are several daily wage workers who would lose out when this land goes to corporates. This loss of livelihood may have to be compensated by the company in terms of employing them in the company or elsewhere and would again require them to train the workers in other skills. The Tatas reportedly plan to train workers for this but past records of most land acquisitions do not give us much of a comfort. We do not have a system to evaluate the effectiveness of the compensation provided and the aftermath of such acquisitions. There have been cases where the displaced receive monetary compensation but their future remains uncertain due to lack of investment knowledge and absence of any other skill sets.

Currently, agricultural land in India cannot be sold for non-agricultural purposes, so such sales happen only when the government comes into the picture by a back door approach of acquiring land from rural areas and selling it to corporates. But should they involve themselves in such transactions only for public utilities like roads, flyovers etc. or should they do this even for sale to private individuals? There may be people who do not wish to sell the space but are forced to do so because the Government thinks it is for the “greater good”.

Do we give farmers the right to sell their land to anyone they wish to? Since right to Property is not a Fundamental right (it was removed under the 44th amendment Act in 1978 by the Janata Party), it becomes an arbitrary call by the government. This naturally depresses the land prices due to lack of buyers and becomes a liability for farmers who want to move out of agriculture. The very idea of this law was to prevent reduction of agricultural land and acquisition of land by loan-sharks and corporates.

However, freeing land sales may also lead to the land going back to the hands of money lenders and zamindars – again a reversal of the process of democratization of land. Moreover, we cannot reduce the worker’s dependence on agriculture suddenly without adequately training him otherwise. And if you train him, will he be gainfully employed?

At a more macro-level, there’s a school of thought which believes that since agricultural productivity is low, the land should be utilized where it gives the best revenue. An argument for effective utilization of resources but I’m not too sure about this approach. A blogger has accused the middle class of romanticizing the notion of rural agriculture when it is totally a loss making concept.

Is agriculture a viable option, especially, considering the dependence of farmers on so many extraneous factors in agriculture like monsoon, price fluctuations, seed quality etc? With stagnant agricultural growth and lack of governmental interest (except in WTO forums and election manifestos), we may require providing farmers with this freedom to sell so that farmlands are easily disposable. This ease of disposal also brings in more buyers and increases the land rates.

However, any such decision must also take into account the social and environmental fallout of rapid and massive industrialization. Somewhere, we need to take a middle path between environmental and economic considerations. We cannot look at either of them in isolation and the challenge is to marry the two interests such that any “collateral damage” is limited. Future wars may be fought on energy and food security, as the Iraqi wars and African conflicts show and we need to be ready for that.

Friday, December 08, 2006

The Great Indian Retail Mela

Ending months of speculation, Bharti has, finally, decided to hitch in with the largest company in the world, Wal-Mart, for its maiden foray into retailing. The American giant beat the British retailing numero uno, Tesco, in this venture- its first ever on Indian shores. The Tesco deal did not come through due to difference in roll-out plans between the two parties. Moreover, Wal-Mart's expertise in running a sophisticated $1.6bn (£830m) sourcing operation in India also helped it to clinch the deal.

All of a sudden, the papers are all about The Great Indian Retail Boom and everyone is vying for a share of the Indian retail pie. This sector is the 2nd largest employer, after the agriculture sector, employing 21 million people, roughly 6% of the country’s total workforce and contributing 13% of the GDP. After being stagnant for years with Lifestyle, Shopper’s Stop, and Pantaloons etc., we are witnessing big players entering the market. The Tatas have recently floated their retail chain, Infiniti Retail, and are collaborating with Australian retailer Woolworth to start their multi-brand durables store, Croma.

The Aditya Birla Group, like Reliance, is going alone and I believe that they have bought space in Punjab for their retail venture. Reliance has, in its characteristic fashion, come up with huge plans – one store in the radius of every 2 km. Its new venture, Reliance Fresh, is currently stocking only vegetables, fruits and diary products but is expected to increase its base slowly, just as Food World had done.

The Indian organized retail market accounts for only 2% of the total retail market as compared to 20% in China. The industry is quite regulated and foreign players cannot directly enter the market. Current norms allow foreign retailers to set up shop in India via the franchisee route, as has been done by the likes of Marks & Spencer and Mango. Foreign retailers are allowed outlets if they manufacture products in India (Benetton) or source their goods domestically. FDI is also permitted in cash-and-carry outlets, where goods are sold only to those who intend using them for commercial purposes (Metro, Shoprite) (Source: The Hindu Business Line).

Retail outlets are, in terms of size, primarily of three types, – you have supermarkets, hypermarkets and the kirana general stores. A hypermarket, pioneered by France’s Carrefour chain, is a supermarket departmental store which carries a huge range of products under its roof, like Giant and Big Bazaar. They occupy huge space and are few in number. Supermarkets, like Reliance Fresh and Food World, are generally smaller and sell primarily household items. They are generally based in residential centres with a decent purchasing power. Kirana stores are the small unbranded departmental stores which are spread everywhere and require less investment.

Returning to the Wal-Mart story, its overseas strategy has been a mixed bag and its struggles in Germany, Japan and Korea have been a cause of concern. A sluggish retail US market has forced it to look overseas, especially the giant Indian and Chinese markets. It has done pretty well in China and is bullish about India too. The market regulations have forced it to enter India as a faceless partner, something it would never have done a few years back.

Wal-Mart’s JV with Bharti entry gives it an opportunity to explore the Indian retail market without too much investment. Bharti has no retail expertise to run this business and therefore, would serve as the front end to the back end logistics support provided by Wal-Mart. This will help Wal-Mart set up shop in future, whenever it chooses to venture out alone and also help in understanding the local culture, which has been its Achilles heel in other markets.

The fear of foreign retailers threatening the local stores is probably unfounded because of the difference in their value propositions and customer segments they cater to. Their entry threatens the bigger Indian players and not the kirana stores. So, the loss of labour point does not stand good; local stores face greater competition from Indian retailers than foreign ones.

For the Indian retailers to succeed, they need to invest in more efficient supply chains, cold chains and increased farmer relationships which call for greater investment which can come through FDI. Increasing real estate prices also calls for heavy investment and the inflows are slow. Footfalls need not translate into revenues and margins are low because of the competition involved and the high fixed costs.

The Food Worlds and Big Bazaars still count on the small base of higher middle classes and upper classes as their customers. While brand loyalty is not a strong factor in the grocery industry, local stores are able to retain their customers because of their personal relationship and rapport with customers. They provide goods on credit to customers and also do free home deliveries. This customer relationship differentiates them from branded retail outlets which are generally frequented by customers, who are willing to pay for the convenience of one-stop shop, the brand value, high end products and the scope for window shopping.

The consumer would eventually benefit because of the choices available to him. There are, of course, fears of predatory pricing (another Wal-Mart’s legacy) and labour problems caused by the entry of foreign players. Wal-Mart’s strategy of “Everyday Low Pricing” has caused a lot of heart-burn not only among local retailers which try to attract customers with promotional strategies and differential pricing but also its suppliers by squeezing them relentlessly. A lot of criticism has also been levelled against the labour and market practices of these big retailers, including low wages, poor work conditions and unhealthy monopolistic practices.

The problems that Indian retailers face would be in finding the right kind of format for the Indian consumer. The Indian consumer is himself not a one-dimensional entity; he has varied tastes dictated by substantial geographical and cultural differences. A Food World in Mumbai may not stock the same products as a Food world in Hyderabad and this may filter down to differences even within its outlets in Hyderabad, say Banjara Hills and Habshiguda. There are also infrastructural problems in terms of parking space, poor logistics and a low focus on CRM which have to be addressed by them.

E-retailing has not caught the fancy of retailers here and the expertise of foreign retailers will help in bridging this technology and supply chain gap. There are also very few players in the semi-urban and rural markets despite all the talk about the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid which clearly suggests a huge untapped market.

So, is there a successful Indian retail model which can be used as the benchmark for all further retailing activities? There may never be so and this, probably, presents the biggest challenge for the Indian retail industry.

All of a sudden, the papers are all about The Great Indian Retail Boom and everyone is vying for a share of the Indian retail pie. This sector is the 2nd largest employer, after the agriculture sector, employing 21 million people, roughly 6% of the country’s total workforce and contributing 13% of the GDP. After being stagnant for years with Lifestyle, Shopper’s Stop, and Pantaloons etc., we are witnessing big players entering the market. The Tatas have recently floated their retail chain, Infiniti Retail, and are collaborating with Australian retailer Woolworth to start their multi-brand durables store, Croma.

The Aditya Birla Group, like Reliance, is going alone and I believe that they have bought space in Punjab for their retail venture. Reliance has, in its characteristic fashion, come up with huge plans – one store in the radius of every 2 km. Its new venture, Reliance Fresh, is currently stocking only vegetables, fruits and diary products but is expected to increase its base slowly, just as Food World had done.

The Indian organized retail market accounts for only 2% of the total retail market as compared to 20% in China. The industry is quite regulated and foreign players cannot directly enter the market. Current norms allow foreign retailers to set up shop in India via the franchisee route, as has been done by the likes of Marks & Spencer and Mango. Foreign retailers are allowed outlets if they manufacture products in India (Benetton) or source their goods domestically. FDI is also permitted in cash-and-carry outlets, where goods are sold only to those who intend using them for commercial purposes (Metro, Shoprite) (Source: The Hindu Business Line).

Retail outlets are, in terms of size, primarily of three types, – you have supermarkets, hypermarkets and the kirana general stores. A hypermarket, pioneered by France’s Carrefour chain, is a supermarket departmental store which carries a huge range of products under its roof, like Giant and Big Bazaar. They occupy huge space and are few in number. Supermarkets, like Reliance Fresh and Food World, are generally smaller and sell primarily household items. They are generally based in residential centres with a decent purchasing power. Kirana stores are the small unbranded departmental stores which are spread everywhere and require less investment.

Returning to the Wal-Mart story, its overseas strategy has been a mixed bag and its struggles in Germany, Japan and Korea have been a cause of concern. A sluggish retail US market has forced it to look overseas, especially the giant Indian and Chinese markets. It has done pretty well in China and is bullish about India too. The market regulations have forced it to enter India as a faceless partner, something it would never have done a few years back.

Wal-Mart’s JV with Bharti entry gives it an opportunity to explore the Indian retail market without too much investment. Bharti has no retail expertise to run this business and therefore, would serve as the front end to the back end logistics support provided by Wal-Mart. This will help Wal-Mart set up shop in future, whenever it chooses to venture out alone and also help in understanding the local culture, which has been its Achilles heel in other markets.

The fear of foreign retailers threatening the local stores is probably unfounded because of the difference in their value propositions and customer segments they cater to. Their entry threatens the bigger Indian players and not the kirana stores. So, the loss of labour point does not stand good; local stores face greater competition from Indian retailers than foreign ones.

For the Indian retailers to succeed, they need to invest in more efficient supply chains, cold chains and increased farmer relationships which call for greater investment which can come through FDI. Increasing real estate prices also calls for heavy investment and the inflows are slow. Footfalls need not translate into revenues and margins are low because of the competition involved and the high fixed costs.

The Food Worlds and Big Bazaars still count on the small base of higher middle classes and upper classes as their customers. While brand loyalty is not a strong factor in the grocery industry, local stores are able to retain their customers because of their personal relationship and rapport with customers. They provide goods on credit to customers and also do free home deliveries. This customer relationship differentiates them from branded retail outlets which are generally frequented by customers, who are willing to pay for the convenience of one-stop shop, the brand value, high end products and the scope for window shopping.

The consumer would eventually benefit because of the choices available to him. There are, of course, fears of predatory pricing (another Wal-Mart’s legacy) and labour problems caused by the entry of foreign players. Wal-Mart’s strategy of “Everyday Low Pricing” has caused a lot of heart-burn not only among local retailers which try to attract customers with promotional strategies and differential pricing but also its suppliers by squeezing them relentlessly. A lot of criticism has also been levelled against the labour and market practices of these big retailers, including low wages, poor work conditions and unhealthy monopolistic practices.

The problems that Indian retailers face would be in finding the right kind of format for the Indian consumer. The Indian consumer is himself not a one-dimensional entity; he has varied tastes dictated by substantial geographical and cultural differences. A Food World in Mumbai may not stock the same products as a Food world in Hyderabad and this may filter down to differences even within its outlets in Hyderabad, say Banjara Hills and Habshiguda. There are also infrastructural problems in terms of parking space, poor logistics and a low focus on CRM which have to be addressed by them.

E-retailing has not caught the fancy of retailers here and the expertise of foreign retailers will help in bridging this technology and supply chain gap. There are also very few players in the semi-urban and rural markets despite all the talk about the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid which clearly suggests a huge untapped market.

So, is there a successful Indian retail model which can be used as the benchmark for all further retailing activities? There may never be so and this, probably, presents the biggest challenge for the Indian retail industry.

Friday, December 01, 2006

Latin America Marches Left

As somebody who takes active interest in world politics, it is impossible not to notice the sweeping change in the world of Latin American politics – the Left is making its strongest ever showing in recent times. Veteran leader Fidel Castro has been replaced by the charismatic Hugo Chavez as the poster boy of this anti-Americanism and this could have interesting implications for the world, especially considering the diminishing stature of the American democracy.

An attempt for an alternate economic and political vision is emerging in the fields of Latin America. A vision which has contempt for American policies, IMF and World Bank strategies is gaining ground and it’s an exciting movement, fostered by the grassroots and people’s movements rather than corporate lobbying. The definition of Leftism, of course, varies from country to country. It probably makes sense to look at this trend not as a Left vs Right issue but as a shift away from a more capitalistic stand, characterized by elitist policies, to an economics dipped in socialism, driven by pro-poor concerns.

Fidel Castro, the old friend of the Yankees, has been its torch bearer for several decades now and has survived more than 50 odd assassination attempts, sponsored by the CIA. But as he grows old, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez has taken over his role as the flag bearer of an alternate economic order, which is different from those dreamt at the corridors of global financial powerhouses. But what has caused this to happen?

The US pumps in a lot of effort and time in promoting US-friendly “democracies” by doling out funds liberally or through coercion (as in Iraq). But the last few years have seen it putting a lot of its energies into tackling Middle East issues. Osama, Saddam and Islamic states, being in the US radar, has meant that Latin America has not been prioritized by them (except for its paranoia towards Chavez). This has resulted in the creation of many groups in Latin America, formed by small farmers, human rights activists, and trade unionists etc. who have a fundamentally different agenda as compared to the industrialized nations - an agenda dictated by local people rather than MNCs.

Moreover, the failure of the US administration policies in fighting drugs and expanding free market reforms have provided further impetus to this. The US administration’s controversial coca eradication strategy, to eliminate the cultivation of coca, as part of its “War on Drugs” policy has alienated people in coca growing areas like Peru, Bolivia and Columbia and the rise of Evo Morales in Bolivia (its first democratically elected indigenous head of state), who is essentially a coca farmer, is testimony to this.

There’s a general disillusionment with the way US has gone about using institutions like World Bank and IMF to further its economic and political interests. More than 30 years back, General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the elected President of Chile, Marxist Salvador Allende, in a bloody coup, covertly backed by the CIA because it would be a blow to Washington's international prestige if an avowed Marxist won a fair presidential election in South America. He held power for the next 17 years, relinquishing control in 1990 only after arranging immunity for himself and his top generals.

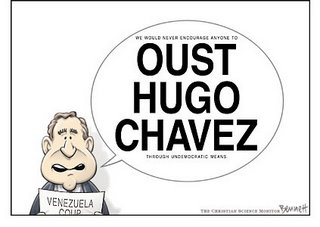

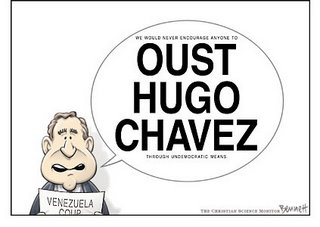

The Bush administration’s animosity towards Hugo Chavez (and the other way around) is quite well known. While US uses all opportunities to paint him as “anti-democratic” (despite winning 2 democratic elections) and uses this as an excuse to foment hatred for him, the world sees it clearly as a combustible conflict being fuelled by America’s vulnerability over Venezuela’s massive oil reserves. It's an open secret that there have been behind the screen attempts by US to rock the Chavez boat, though denied repeatedly by the administration.

The World Bank and IMF are not exactly the most popular institutions in the minds of developing nations. Rather than being seen as welfare financial institutions, they are increasingly being perceived as Shylock styled-creditors out to extract their pound of flesh. Nobel Laureate and former Chief Economist at the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz, says one of the main problems with IMF is that it believes in a one-stop shop treatment for all economic problems facing the world and blasts it for being every bit as secretive, undemocratic and indifferent to the poor as its critics claimed.

All that the IMF seems to be bothered is fiscal deficit management through decreased govt. spending on social programmes, greater privatization and facilitation of international trade, irrespective of the problem. They conveniently forget that any such kind of reduced government spending affects the poor the most. UN estimates say that Latin America has the most unequal wealth distribution of any region in the world, despite religiously sticking to the prescriptions given by the IMF and World Bank. This kind of increased intolerance to the local needs has led to countries veering away from these institutions.

Argentina, under Nestor Kirchner, has recovered remarkably after its economic collapse in 2001 by greater public investment, hard bargaining with private creditors and has gone to the extent of prepaying its entire debt to the IMF by borrowing from Venezuela, to free itself from the IMFs clutches.

Under pressure from the World Bank, the Bolivian government in 2000 sold off Cochabamba's (its third largest city) public water system to Bechtel subsidiary Aguas Del Tunari. Within weeks of taking control of the city's water, Bechtel hit poor families with huge increases in their water bills, enough to spark a popular rebellion and chase Bechtel out of the country. This was followed by another controversial deal in 2003 where the country’s natural gas was sold off to California through a private consortium, Pacific LNG, at a pittance. The great civil conflict that arose because of this led to the resigntion of two Presidents and eventually the nationalization of all gas reserves in Bolivia in May 2006.

All these changes have seen a dramatic shift in world politics, currently dwarfed by the events in Middle East and parts of Asia. Countries like Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela and others are working together to foster a spirit of Latin American unity to fight the might of US and other global financial powerhouses. The focus is moving to the state and people determining the economic policies being framed rather than being dictated by colonial powers and private lobby houses which have their own vested interests.

There will always be conflicts when corporations try to use their clout and lobbying power to bag contracts heavily skewed in their favour and neglect the needs of the local population. The resultant exploitation of local conditions for greater profit making will eventually lead to a backlash against the company. Closer back home, Coca-Cola signed a deal with the Kerala Government to extract water at very low prices. The result was depletion and contamination of ground water in Plachimada in Palakkad District; so while agriculture suffered due to paucity of water, Coke was making heavy profits by selling at about 10 Rs per bottle. Hopefully, we would learn from the Latin American countries and standing up for the rights of our people.

Will this movement change the way the world moves? Can problems of poverty and malnourishment be solved by these countries by giving a human face to economic reforms or is this an aberration driven by a few leaders? Only time will tell but this is a transition we must observe carefully and it has wide repercussions in the global balance of power. As Atila Roque, Executive Director of ActionAid USA, says, “Democracy must go beyond elections of the President and Parliament. Democracy is the freedom to make innovative economic decisions that will improve people’s lives”.

As I began writing this article, news came in that Ecuador has also elected a Leftist Government led by economist Rafel Correa. One more state down.......

An attempt for an alternate economic and political vision is emerging in the fields of Latin America. A vision which has contempt for American policies, IMF and World Bank strategies is gaining ground and it’s an exciting movement, fostered by the grassroots and people’s movements rather than corporate lobbying. The definition of Leftism, of course, varies from country to country. It probably makes sense to look at this trend not as a Left vs Right issue but as a shift away from a more capitalistic stand, characterized by elitist policies, to an economics dipped in socialism, driven by pro-poor concerns.

Fidel Castro, the old friend of the Yankees, has been its torch bearer for several decades now and has survived more than 50 odd assassination attempts, sponsored by the CIA. But as he grows old, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez has taken over his role as the flag bearer of an alternate economic order, which is different from those dreamt at the corridors of global financial powerhouses. But what has caused this to happen?

The US pumps in a lot of effort and time in promoting US-friendly “democracies” by doling out funds liberally or through coercion (as in Iraq). But the last few years have seen it putting a lot of its energies into tackling Middle East issues. Osama, Saddam and Islamic states, being in the US radar, has meant that Latin America has not been prioritized by them (except for its paranoia towards Chavez). This has resulted in the creation of many groups in Latin America, formed by small farmers, human rights activists, and trade unionists etc. who have a fundamentally different agenda as compared to the industrialized nations - an agenda dictated by local people rather than MNCs.

Moreover, the failure of the US administration policies in fighting drugs and expanding free market reforms have provided further impetus to this. The US administration’s controversial coca eradication strategy, to eliminate the cultivation of coca, as part of its “War on Drugs” policy has alienated people in coca growing areas like Peru, Bolivia and Columbia and the rise of Evo Morales in Bolivia (its first democratically elected indigenous head of state), who is essentially a coca farmer, is testimony to this.

There’s a general disillusionment with the way US has gone about using institutions like World Bank and IMF to further its economic and political interests. More than 30 years back, General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the elected President of Chile, Marxist Salvador Allende, in a bloody coup, covertly backed by the CIA because it would be a blow to Washington's international prestige if an avowed Marxist won a fair presidential election in South America. He held power for the next 17 years, relinquishing control in 1990 only after arranging immunity for himself and his top generals.

The Bush administration’s animosity towards Hugo Chavez (and the other way around) is quite well known. While US uses all opportunities to paint him as “anti-democratic” (despite winning 2 democratic elections) and uses this as an excuse to foment hatred for him, the world sees it clearly as a combustible conflict being fuelled by America’s vulnerability over Venezuela’s massive oil reserves. It's an open secret that there have been behind the screen attempts by US to rock the Chavez boat, though denied repeatedly by the administration.

The World Bank and IMF are not exactly the most popular institutions in the minds of developing nations. Rather than being seen as welfare financial institutions, they are increasingly being perceived as Shylock styled-creditors out to extract their pound of flesh. Nobel Laureate and former Chief Economist at the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz, says one of the main problems with IMF is that it believes in a one-stop shop treatment for all economic problems facing the world and blasts it for being every bit as secretive, undemocratic and indifferent to the poor as its critics claimed.

All that the IMF seems to be bothered is fiscal deficit management through decreased govt. spending on social programmes, greater privatization and facilitation of international trade, irrespective of the problem. They conveniently forget that any such kind of reduced government spending affects the poor the most. UN estimates say that Latin America has the most unequal wealth distribution of any region in the world, despite religiously sticking to the prescriptions given by the IMF and World Bank. This kind of increased intolerance to the local needs has led to countries veering away from these institutions.

Argentina, under Nestor Kirchner, has recovered remarkably after its economic collapse in 2001 by greater public investment, hard bargaining with private creditors and has gone to the extent of prepaying its entire debt to the IMF by borrowing from Venezuela, to free itself from the IMFs clutches.

Under pressure from the World Bank, the Bolivian government in 2000 sold off Cochabamba's (its third largest city) public water system to Bechtel subsidiary Aguas Del Tunari. Within weeks of taking control of the city's water, Bechtel hit poor families with huge increases in their water bills, enough to spark a popular rebellion and chase Bechtel out of the country. This was followed by another controversial deal in 2003 where the country’s natural gas was sold off to California through a private consortium, Pacific LNG, at a pittance. The great civil conflict that arose because of this led to the resigntion of two Presidents and eventually the nationalization of all gas reserves in Bolivia in May 2006.

All these changes have seen a dramatic shift in world politics, currently dwarfed by the events in Middle East and parts of Asia. Countries like Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela and others are working together to foster a spirit of Latin American unity to fight the might of US and other global financial powerhouses. The focus is moving to the state and people determining the economic policies being framed rather than being dictated by colonial powers and private lobby houses which have their own vested interests.

There will always be conflicts when corporations try to use their clout and lobbying power to bag contracts heavily skewed in their favour and neglect the needs of the local population. The resultant exploitation of local conditions for greater profit making will eventually lead to a backlash against the company. Closer back home, Coca-Cola signed a deal with the Kerala Government to extract water at very low prices. The result was depletion and contamination of ground water in Plachimada in Palakkad District; so while agriculture suffered due to paucity of water, Coke was making heavy profits by selling at about 10 Rs per bottle. Hopefully, we would learn from the Latin American countries and standing up for the rights of our people.

Will this movement change the way the world moves? Can problems of poverty and malnourishment be solved by these countries by giving a human face to economic reforms or is this an aberration driven by a few leaders? Only time will tell but this is a transition we must observe carefully and it has wide repercussions in the global balance of power. As Atila Roque, Executive Director of ActionAid USA, says, “Democracy must go beyond elections of the President and Parliament. Democracy is the freedom to make innovative economic decisions that will improve people’s lives”.

As I began writing this article, news came in that Ecuador has also elected a Leftist Government led by economist Rafel Correa. One more state down.......

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)